All of us are familiar with Jesus’ teachings about peacemaking: “Blessed are the peacemakers.” Peacemaking is a path to being called children of God (Mt. 5:9). Likewise, Paul exhorts us to peacemaking: “If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone” (Rom. 12:18).

And then along comes Veterans Day.

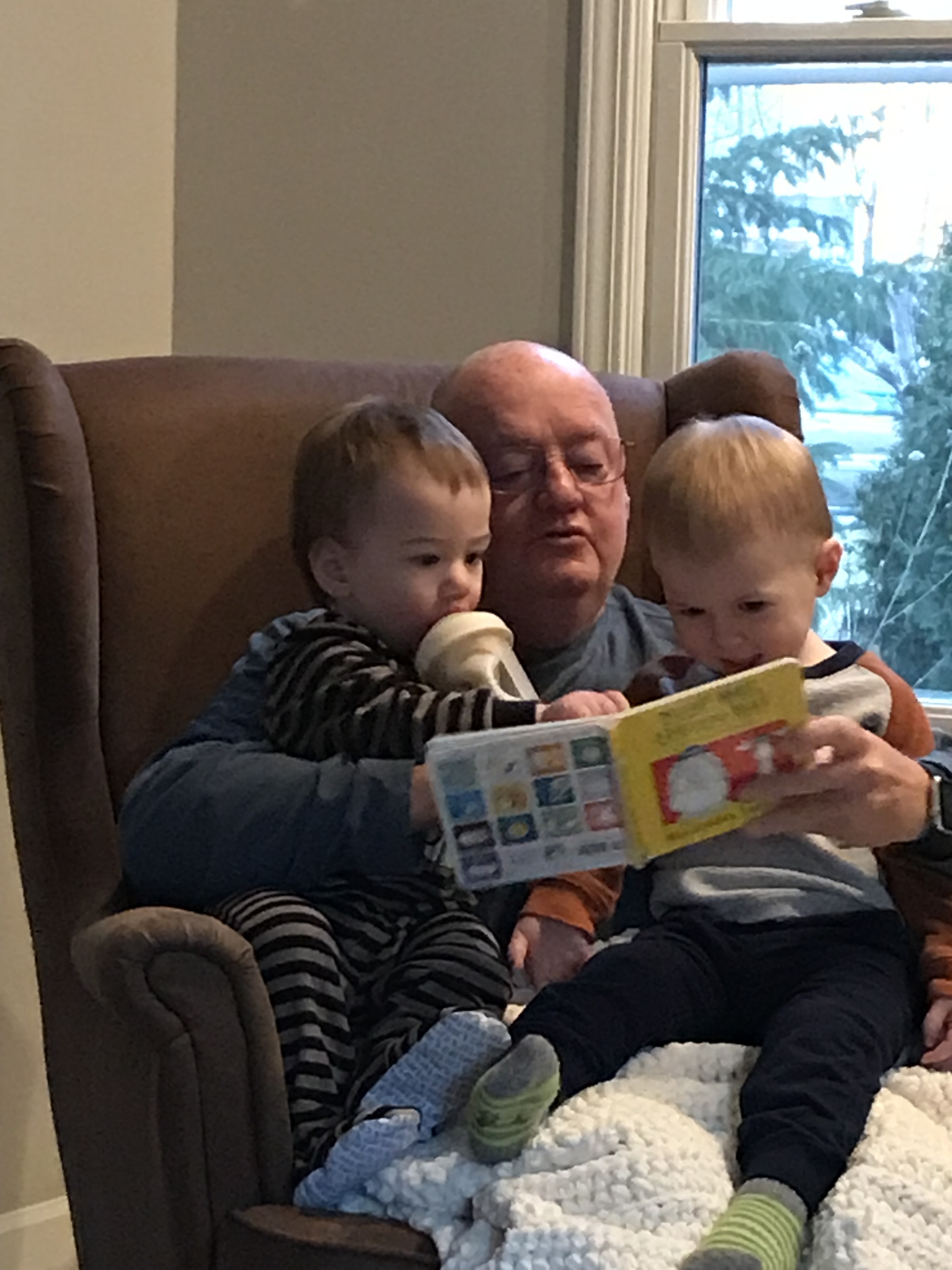

Many of us have beloved family members who are veterans. Many have family and friends who are active duty military. So, how do we love our soldiers and still obey the Christian commands to peacemaking? The simplistic answer is that soldiers are peacemakers, that wars are fought to bring peace. Were that always true! Yet, many wars are fought for less noble reasons, such as James notes, “What causes fights and quarrels among you? Don’t they come from your desires that battle within you? You desire but do not have, so you kill. You covet but you cannot get what you want, so you quarrel and fight” (Ja. 4:1-2).

So, if we believe in peacemaking, are we required to be anti-soldiers? By no means!

In fact, Paul, who argues for peacemaking, likes to use soldiers as a positive metaphor: “Join with me in suffering, like a good soldier of Christ Jesus” (2 Tim. 2:3).

How do we respect veterans and honor the sacrifices of our soldiers, and yet speak for peace? More significantly, how can a Christian critique a particular war without being considered a soldier-hater or accused of not being patriotic?

It can start by recognizing an important truth.

Soldiers don’t decide about wars. The decision to go to war is made by elected civilians. A soldier does not have the right to decide whether a war is just. Such would be treason (in addition to chaos). Soldiers do as they are commanded. Obedience is an essential element of soldiering.

Debating the justice of a war is independent of loving and supporting our soldiers. If I were to say that a particular war in such-n-such a place is unjust and we have no business being there, I am NOT critiquing the soldiers who are sacrificing to be there. I am not belittling the families who are undergoing hardships because their soldier is there. Rather, I am critiquing Congress. Soldiers didn’t decide to go there; Congress decided to send them here. Tomorrow, the soldier may be deployed elsewhere. Congress may announce that yesterday’s enemies are today’s allies. If so, the soldier climbs out of one foxhole and into the other. The person he was shooting at yesterday is now the person he is training today. Tomorrow, Congress may announce that they are the “enemy” again. In any case, soldiers do as commanded. Paul notes a soldier works “to please his commanding officer” (2 Tim. 2:4). Ironically, wars are civilian matters, even when soldiers are the ones carrying it out.

Loving our soldiers, supporting our military, and honoring our veterans should be done. Yet they must never be used as a hammer to silence Christians on peacemaking. Speak up for peace. Speak your convictions about whether we should or should not be engaged in a particular war. Critiquing a war is not critiquing soldiers, but a civilian decision. It is possible to honor our veterans without glorifying war.

Honor our vets today and with the same breath, speak for peace.

Leave a comment